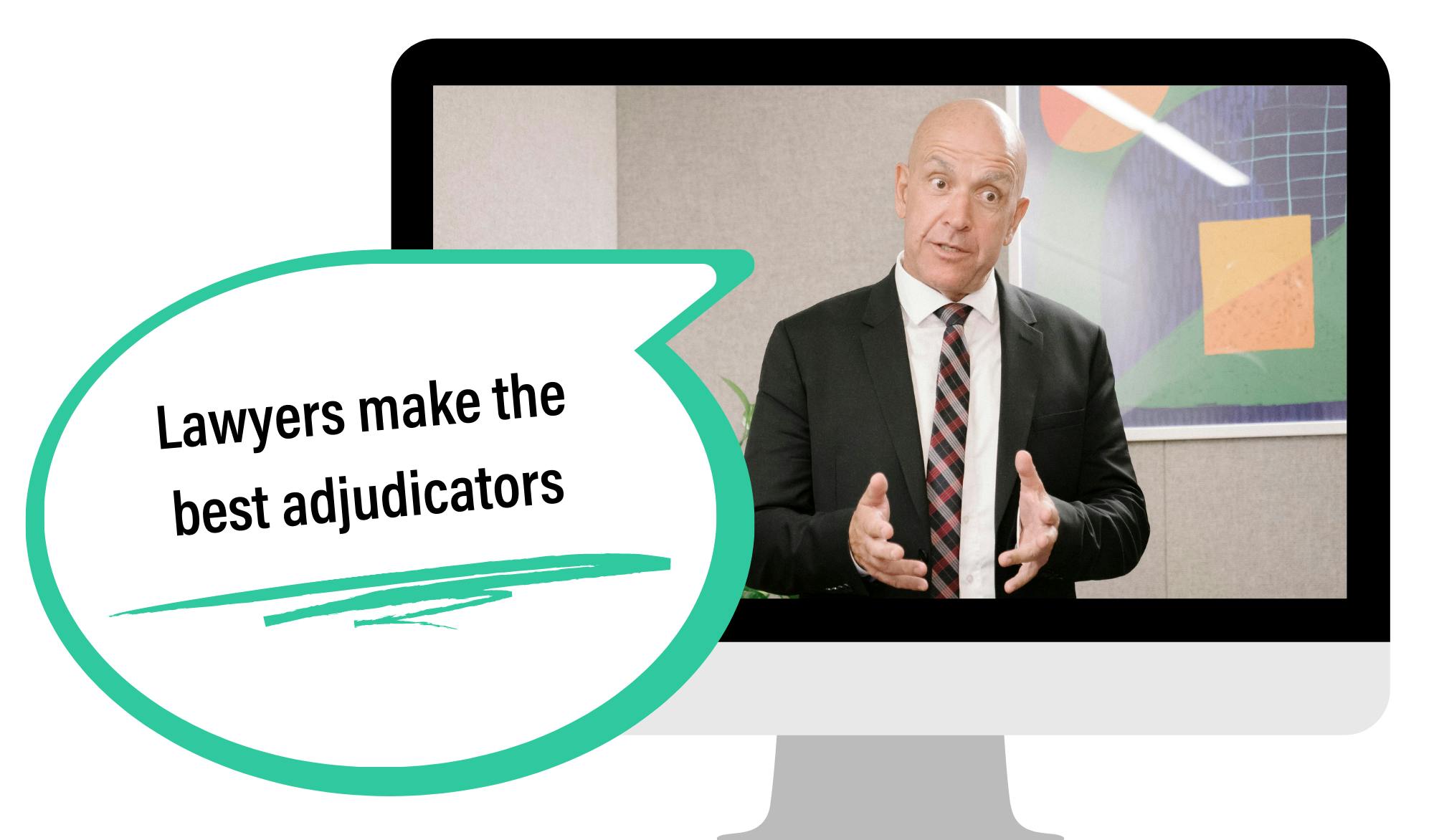

Recently Michael Chesterman and I participated in a RICSDRS CPD event where we debated an issue that has divided consumers on the adjudication process, namely ‘Do lawyers make the best adjudicators?’

For this event, we decided to make things interesting and challenge ourselves to argue against our instinctive positions. Consequently, Michael, as a non-lawyer argued in the affirmative and I, as an experienced construction lawyer, with the greatest respect to my colleagues, argued that lawyers do not make the best adjudicators.

For the purposes of this article, we have applied the analysis undertaken by us and pose to you the question of – what makes a good adjudicator?

I believe practical, suitably qualified, experienced, fair, bold, and decisive people make the best adjudicators. I know of many lawyers that fit this description because they have adapted to the unique role of an adjudicator. However, some lawyers are very risk-averse, extremely cautious in everything they do, and in my view incapable of adapting to the pressure cooker environment of adjudication.

Lawyers are taught to conduct research and analysis of legal problems. Interpret laws, rulings, and regulations. Good lawyers are great inquisitors.

Subject to finding jurisdiction, an adjudicator must decide a payment claim entitlement of a claimant, in sometimes less than perfect circumstances. In the video below, we explain the circumstances where jurisdiction might be challenged.

Adjudicators must not enquire into disputes. Rather, they must decide matters based on the material presented by the parties. For some lawyers, this is a bridge too far in adapting to becoming good adjudicators.

Furthermore, the ‘adjudication hot house’ requires a certain type of adjudicator because of the unique characteristics of adjudication.

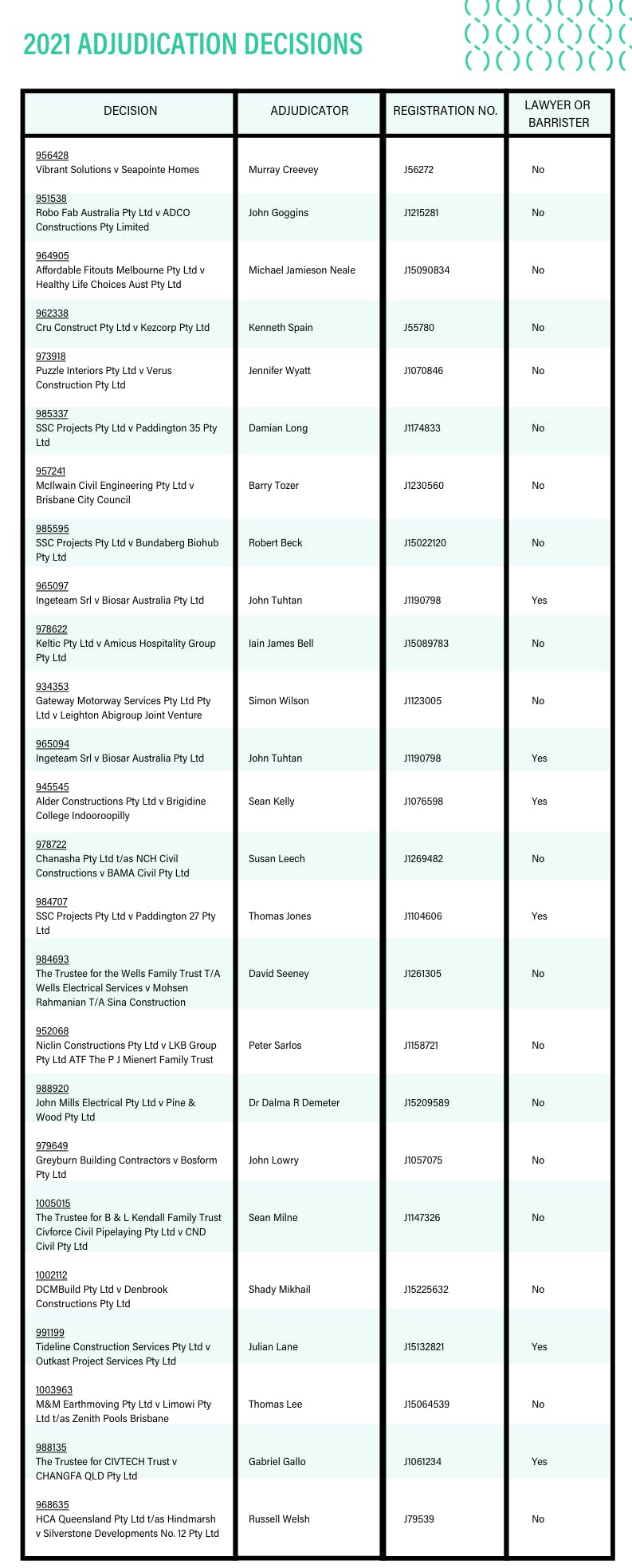

Of the decisions published to 16 March 2021 by the Adjudication Registry in 2021, 24% were decided by lawyers or barristers. Of the decisions made by the lawyers or barristers:

- 67% of the decisions were complex claims;

- 33% of the decisions were standard claims;

- 17% awarded the full claimed amount; and

- 100% found jurisdiction to decide the application.

Of the decisions made by the non-lawyers:

- 26% of the decisions were complex claims;

- 74% of the decisions were standard claims;

- 32% awarded the full claimed amount; and

- 79% found jurisdiction to decide the application.

Of the 21% of decisions by non-lawyers that were found not to have jurisdiction, 75% of the decisions were for standard claims.

While I acknowledge that each case has its own individual characteristics, these figures indicate a trend this year towards lawyers being allocated more complex decisions. Based on this very small snapshot of data, lawyer adjudicators also appear less likely to award the full claimed amount.

In all 2021 decisions, an amount was awarded where jurisdiction could be established.

Click here to download a PDF version and access the links to all adjudication decisions above.

Put simply, those wanting to be paid could either move on with life or go to Court. While adjudication does not profess to have all the protections and checks and balances of Court there can be no question, even in the face of more complicated and higher value adjudications we see today, it still brings about an outcome at the lower cost and in a shorter amount of time. I support a system with a pool of adjudicators of different backgrounds and experience but with a consistent base of knowledge maintained through CPD as an appropriate solution to meeting the requirements of the adjudication process. Adjudication is an imperfect solution to an age-old problem and a less legalistic and more practical approach may be called for depending on the circumstances of the dispute. It is well accepted that it was necessary for adjudication to be introduced back in 2004 because of the power imbalance in the contractual chain.

So, what makes a good adjudicator?

As a non-lawyer, I look at adjudication in Queensland in very simple terms. In order to determine what makes a good adjudicator we need to consider the nature of what adjudication actually is. In an earlier article ‘Back to basics’ adjudication for an economy in hibernation, I stated:

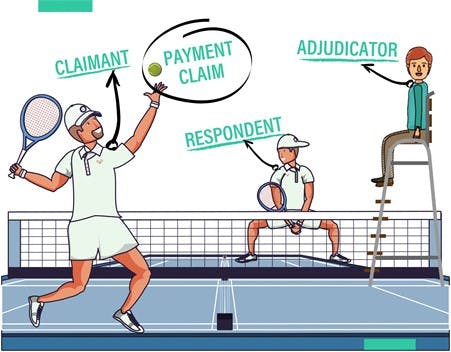

“I like to explain adjudication in terms of a game of tennis between a subcontractor as a claimant and a head contractor as the respondent. I should make the point that this simple analogy reflects what most commonly happens in adjudication.

The subcontractor gets to serve a payment claim, setting out the amount claimed and a description of the works.

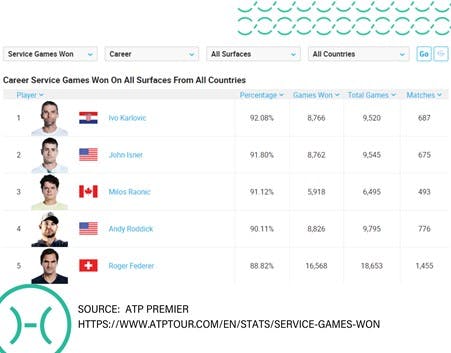

Only a claimant ever gets to serve a payment claim. This represents a huge advantage for claimants. Just to lighten things up a bit, I googled career service games won on all surfaces, from all countries, by top men players. Roger Federer has 88.82% as just one example.”

What transpires after the serving of a payment claim by a claimant, is a limited series of back-and-forth documents, with the adjudicator having to quickly decide the outcome of the dispute. On 16 March 2021, I argued in the RICSDRS debate that lawyers are well suited to this but it may be just as readily argued that lawyers are taught to inquire and research for themselves which is arguably the opposite of what adjudication requires.

The reality is that claimants are granted significant statutory advantages in adjudication. In this sense, it is unlike any other dispute resolution process. While the winners might agree that the adjudicators who award the most money are the best adjudicators, for every winner, there is a loser who will disagree. In most adjudications decisions, it is likely that 50% will find the adjudicator lacking and 50% will be satisfied.

In the context of my tennis analogy, claimants are allowed to get on the front foot by serving payment claim after payment claim. Respondents are always on the back foot defending their payment position. I am aware that some lawyers find this fundamental plank of the Queensland statutory adjudication regime (East Coast Model), grossly unfair to respondents.

In conversations I have had with some of these lawyers, they view the West Coast Model of adjudication in a much more favourable light. This is because, under the West Coast Model, parties are provided with a statutory rapid adjudication process that enables either party to enforce all of their contractual rights, not just the enforcement of a party’s entitlement to payment.

Any party to a construction contract may make an application for adjudication up and down the contractual chain regardless of whether they are a claimant or a respondent. In the video below, former Adjudication Registrar, Cheriden Farthing, describes the broad scope of who can lodge an adjudication application and that you can lodge an adjudication application with the registry if you do not have a QBCC licence.

Adjudication in Queensland has also been described as a ‘quick and dirty’ process. I prefer to describe it as uncompromising in its repudiation of unfair delaying tactics employed by some parties to pay claimants for work done or goods or services provided.

Consequently, the Queensland version of adjudication is unashamedly a brash dispute process, with no time for what I call legal niceties like adjournments of postponements.

Adjudication is a high pressure, speedy, high stakes dispute process. Consequently, adjudicators must be bold and decisive in deciding payment disputes, in the process not falling foul of inquiring into the dispute.

Lawyers and non-lawyers both have a role in Adjudication.

As the inaugural Adjudication Registrar (2004-2017), I was very keen on ensuring that people with suitable qualifications other than of a legal nature, and providing they obtained the required Adjudication Qualification, could become adjudicators.

If you are a respondent contractor that works across the country with a focus on Queensland, your team will benefit from the Helix SOP Online Course. This training is designed to help you understand the SOP rules and requirements that relate to Queensland, as well as understanding the Adjudicators’ jurisdiction to adjudicate and how to identify jurisdictional errors.

Not intended as legal advice. Read full disclaimer.